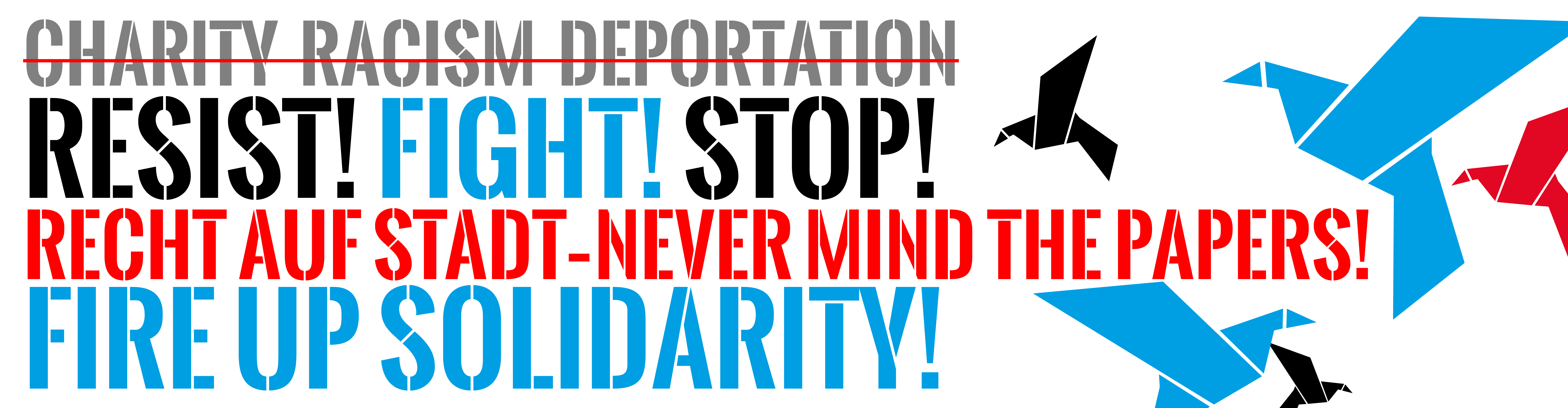

Erklärung des Plenums des Hamburger Recht auf Stadt-Netzwerks und des Bündnisses “Recht auf Stadt – never mind the papers!”: Was wir am derzeitigen Notstandsurbanismus kritisieren und warum wir einen „Volksentscheid gegen Großunterkünfte“ für Flüchtlinge für falsch halten. (English below)

1. Ein Volksbegehren über Wohnunterkünfte für Geflüchtete, bei dem die Geflüchteten nicht abstimmen können? Geht gar nicht.

Asylbewerberinnen und -bewerber sind nicht wahlberechtigt und können bei einem Volksentscheid nicht mitmachen. Die Anwohnerinnen und Anwohner, die sich in den „Initiativen für Integration“ organisiert haben, erklären zwar, sie handelten auch „im Interesse der Flüchtlinge”, wenn sie gegen den Bau von Großsiedlungen vorgehen. De facto bleiben die Geflüchteten ausgesperrt. Ein solcher Volksentscheid ist ein Angriff auf die elementaren Rechte der Geflüchteten – und ein Angriff auf das Recht auf Stadt.

2. Die Not in den Lagern duldet keinen Aufschub

Die elende Situation in den Containern, Lagerhallen, Ex-Baumärkten und anderen Massenunterkünften muss so schnell wie möglich behoben werden. Auch wenn wir Kritik an der Ausgestaltung der Planung haben: Es ist eine richtige Entscheidung, dass der Hamburger Senat schnell agiert. Hamburg braucht bis 2016 rund 79.000 Plätze. Und das ist nur die offizielle Zahl. Die Not in den Lagern muss durch Umbau von Bestand und durch Neubau behoben werden. So schnell, so viel, so zentral, so hoch wie eben nötig und möglich.

3. Die Gegenvorschläge können die Notmaßnahmen nicht ersetzen.

Um das zu erreichen, kann es auch angemessen sein, Wohnungen per Polizeirecht durchzusetzen. Verließe sich der Senat allein auf das normale Planrecht, könnte es Jahre dauern, bis die benötigten Unterkünfte gebaut würden. Dass es viele gute Gründe gibt, skeptisch gegenüber den neuen Wohnsiedlungen zu sein, ist unbenommen. Sie liegen zumeist am Stadtrand, sind architektonisch oft eher einfallslos, man hat bisher zu wenig Anstrengungen unternommen, um die Communities vor Ort zu involvieren – schon gar nicht die Refugees, die hier wohnen sollen. Trotzdem: Die Gegenvorschläge der protestierenden Anwohnerinnen und Anwohner und der in der IFI organisierten Inis reichen nicht, um die Geflüchteten mit Wohnraum zu versorgen. Ein „Viertelmix“ im Geschosswohnungsbau (25% Wohnungen für Geflüchtete) oder die „Angebote der Grundeigentümer“, die die Stadt angeblich ausschlägt, sind allenfalls eine Ergänzung zu den notwendigen Baumaßnahmen – und als solche müssen sie ernsthaft diskutiert werden, genau so wie die Flächen, die die Initiativen vorschlagen. Aber: Mit einer „Überall bloß nicht hier“-Haltung ist ein Volksentscheid nichts anderes als eine lokale Obergrenzen-Diskussion.

4. Ein Referendum wird die Unterkünfte nicht verhindern

Optimistisch geschätzt kann ein Volksentscheid frühestens im kommenden Frühjahr abgestimmt werden, womöglich erst zur Bundestagswahl im Herbst 2017. Dann werden – hoffentlich – längst Menschen in die neuen Unterkünfte eingezogen sein, zumindest aber werden sie baurechtlich nicht mehr anfechtbar sein. Sprich: Die Kampagne zum Volksentscheid wird die geplanten Wohnanlagen nicht verhindern können – allerdings eine Menge Stimmung gegen sie machen.

5. Kampagnen gegen Refugee-Unterkünfte ziehen Rechtspopulisten und Rassisten an.

Die Initiativen gegen die Großsiedlungen betonen immer wieder, sie hätten nichts gegen Geflüchtete und setzten sich vielmehr für „integrationspolitisch sinnvolle und nachhaltige Maßnahmen zur Flüchtlingsunterbringung“ ein. Mit der AfD wollen sie nicht nicht reden. Das begrüßen wir – und wir halten es auch für unangebracht, die Initiativen a priori als rassistisch oder rechtsradikal zu stigmatisieren. Dennoch erleben wir in all den Stadtteilen, in denen die neue Bürgerbewegung sich organisiert, wie Leute unwidersprochen rassistische Ressentiments in die Anhörungen und Versammlungen hineintragen und damit das Klima beeinflussen. Sich von der AfD und Rechtsradikalen abzugrenzen, aber ihren Positionen ein Forum zu bieten: Das geht nicht in Ordnung.

6. Die Rede von Ghettos ist leichtfertig und hysterisch

Es gibt seit Jahren in Hamburg einen massiven Verdichtungsprozess, dem Hinterhöfe und Naturflächen zum Opfer fallen. Bisweilen haben sich gegen einzelne Bauvorhaben auch Proteste in den Stadtteilen geregt. Doch die Massivität, mit der Anwohnerinnen und Anwohner nun gegen Bauvorhaben für Geflüchtete auf die Barrikaden gehen, sucht ihresgleichen. „Parallelgesellschaften in städtischen Ghettos müssen verhindert werden“, schreiben die Initiativen. Egal, ob in Klein Borstel, Ottensen oder Eppendorf Wohnungen für 700, 850 oder 2000 Geflüchtete geplant sind oder ob in einer weniger gutsituierten Gegend wie Neugraben-Fischbek 4000 Menschen leben sollen: Immer sprechen die Protest-Inis von „Ghettos“ und fordern eine gleichmäßigere Verteilung der Unterkünfte auf alle Stadtteile. Wir plädieren an dieser Stelle für weniger Hysterie. Ein paar hundert oder tausend Menschen machen noch kein Ghetto. Wer es dennoch so sehen will, diffamiert ganze Communities. Wir wissen auch: Es ist offensichtlich schwerer, in den wohlsituierten Stadtteilen Unterkünfte für Geflüchtete durchzusetzen, wo man sich die besseren Rechtsanwälte leisten kann und wo die Grundstückspreise astronomisch sind. Dass sich in den „Initiativen für Integration“ jetzt Wohlstandsenklaven und Kleine-Leute-Stadtteile zusammenschließen, macht die Verteilung aber auch nicht gerechter. Wir befürchten: Egal wo die Stadt Unterkünfte bauen will – immer werden sie vor Ort auf Leute treffen, die das für unzumutbar halten.

7. Weder Ghetto-Panik noch Notstandsplanung: Wir brauchen einen anderen Urbanismus.

Dass Politiker, Planer und Architekten jahrzehntelang keine Konzepte für bezahlbares, gutes und nachhaltiges Bauen gemacht haben, dass sozialer Wohnungbau in Deutschland im wesentlichen ein Investoren-Förderprogramm ist (kein anderes europäisches Land macht das so): All das rächt sich nun. Es muss eine Alternative her. Zu einer urbanen Strategie, die in der jetzigen Lage greift, gehört eine neue Haltung. Weg von Ghetto-Panik, hin zu den Möglichkeiten und Chancen für die neuen Nachbarschaften. Nähstuben für Refugees und einheimische Anwohnerinnen und Anwohner, selbstgegründete Kioske, Läden mit arabischen Spezialitäten, Nachbarschafts-Cafés, Start-Ups, lokale Kleiderkammern oder Werkstätten: Auch in den jetzt schnell hochgezogenen Projekten müssen Erdgeschosse für solche Nutzungen freigehalten werden. Wir brauchen Flexibilität, um informelle Strukturen zuzulassen, damit lebendige Stadtteile entstehen können, die den Communities und ihren Nachbarinnen und Nachbarn neben Wohnraum auch Treffpunkte, Platz für Experimente und Gründungen bietet.

8. Keine Beteiligung ist auch keine Lösung

Trotz aller Warnungen und Prognosen von Migrationsforschern und Hilfsorganisationen sind die Städte nicht vorbereitet auf die Refugees, die Deutschland derzeit erreichen. Ihr Notstandsmanagement war bisweilen skandalös und oft agierten sie unglücklich im Umgang mit der Zivilgesellschaft. Diese Erfahrung haben viele Ehrenamtliche gemacht, die im Sommer 2015 selbstorganisiert das Schlimmste auffingen – am Lageso in Berlin genauso wie in der ZEA Hamburg-Harburg oder in den Hallen-Notunterkünften. Menschen, die den überforderten Behörden und Trägern mit unermüdlichem Einsatz den Arsch retteten, wurden wie lästige Bittsteller abgefertigt. Dass die Anwohnerinnen und Anwohner der zukünftigen Großsiedlungen sich über die Arroganz der Macht beschweren, hat Gründe. Ein schroffer Anti-Beteiligungskurs verschärft die Konflikte bloß und ist angesichts der Versäumnisse unangemessen. Stattdessen sollten die Projekte unter Teilhabe der selbstorganisierten Hilfsnetzwerke und der Anwohnerinnen und Anwohnerinnen entwickelt werden. Und selbstverständlich müssen auch die Refugees in die Entwicklung einbezogen werden, statt sie als passive Hilfeempfänger zur Unmündigkeit zu degradieren. Es braucht engagierte Planungsverfahren, mit Beteiligung von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern, urbanen Designern, Studierenden, Menschen aus sozialen Berufen, Ehrenamtlichen und Nachbarschaftsinitiativen. Aus dem Hamburger Recht auf Stadt-Kontext entstandene Projekte wie die Planbude, aber auch das Gängeviertel und die fux-Genossenschaft machen deutlich, dass eine kollektive Planung zu besseren Ergebnissen führt. Projekte wie das Grandhotel Cosmopolis Augsburg, Haus der Statistik Berlin oder Neue Nachbarschaft Moabit sind Modelle, die ernst genommen und in die Überlegung einbezogen werden müssen. In Hamburg haben Refugee Welcome Karoviertel, die Kleiderkammer die Helfergruppe Hauptbahnhof neben anderen gezeigt, dass selbstorganisierte Strukuren gelegentlich besser funktionieren als der Behördenapparat – sie müssen einbezogen werden.

9. Haben wir ein „Flüchtlingsproblem“? Wir haben ein Wohnungsproblem!

Die derzeitige Planung bleibt, was das Denken über Stadt, Raum, sozialen Raum betrifft, weit hinter den technischen und materiellen Möglichkeiten, hinter dem gesellschaftlichen Reichtum zurück. Die Hamburger Olympia-Bewerbung hat die Visionslosigkeit der Stadt mit der Hoffnung auf ein Megaevent überpinselt, aber die Leere nicht gefüllt. Über Jahrzehnte hat die Politik den Wohnungsnotstand in den Großstädten ignoriert, ja gefördert. Bis tief in die Mittelschichten hinein wird es immer schwieriger, angemessenen Wohnraum zu finden. Das Marktversagen ist seit langem offensichtlich, und die Wohnungskrise betrifft besonders die Armen. Für die hierher Geflüchteten und Papierlosen ist die Situation dramatisch, oft unerträglich und elend. Das derzeitige Programm bringt noch keine Wende in der Wohnungspolitik. Mit dem 20 Milliarden-Programm der Bundesregierung wird wieder Steuergeld in die Immobilienbranche gepumpt – und verschleudert. Stattdessen muss diese Investition Wohnraum schaffen, der auf Dauer niedrige Mieten sichert. Aus dem Wohnungsbau für Geflüchtete muss schnell ein Wohnbauprogramm für alle mit wenig Geld werden, es muss gemeinnützige Genossenschaften, Stiftungsmodelle, alternative Investoren wie das Mietshäusersyndikat ins Boot holen und neue Konzepte für öffentliches Eigentum entwickeln. Pragmatismus bei der Schaffung von Wohnraum ist gut. Dazu gehört neben den Schnell- und Neubauten aber auch ein pragmatischer Umgang mit dem Bestand. Der Abriss des City-Hofes ist derzeit nicht vorrangig, stattdessen könnte man das Axel Springer Haus zu einer zentral gelegenen Unterkunft machen – ebenso wie etwa die leerstehende Postpyramide in der City Nord. Wir brauchen eine mutige, entschlossene Politik bei der Frage, wie man unkonventionell und schnell Bestandsbauten umwandelt und nutzt.

10. Geflüchtete haben ein Recht auf Stadt

Ein Volksentscheid gegen Großunterkünfte ist keine Lösung. Wir meinen: Lasst das sein! Hamburg braucht weder lokale Seehofers im Integrationsgewand, noch im Windschatten segelnde Rechtsradikale. Distanziert euch! Der Volksentscheid befördert die falsche Debatte – nämlich eine, die Geflüchtete nur als Belastung taxiert. Was wir stattdessen brauchen, sind Bauvorhaben, die einen Mehrwert für die Viertel bieten, die Raum für informelle Aneignung durch die Nachbarschaft schaffen, die Kontaktflächen und Plattformen des Austauschs haben. Lasst uns gemeinsam innovative Lösungen entwickeln, mit Pragmatismus und mutigen Visionen für ein dauerhaft sozial abgesichertes Wohnen in einer Stadt, die sich ändern muss und wird. Ein Großteil der Refugees wird bleiben und Teil unserer Stadt werden. Sie haben ein Recht auf Stadt. Treiben wir die Politik zu einer Planung, die uns und unseren neuen Nachbarinnen und Nachbarn Räume, Teilhabe und Entwicklung ermöglicht, und bieten wir dem brutalisierten Selbstmitleid des AfD-Milieus die Stirn.

Wir schaffen das? Nein, wir wollen das. Und wir wollen eine Stadt, die das will.

Plenum des Hamburger Recht auf Stadt-Netzwerks, 9. Februar 2016

Plenum des Bündnisses “Recht auf Stadt – never mind the papers!”, 10. Februar 2016

———————————–

Migration meets the city.Against hysteria – for a different urban planning

Resolution of the plenum of the Right to the City Network Hamburg and the alliance “Recht auf Stadt – never mind the papers!”: 10 theses against the current emergency urbanism and a planned referendum against refugee housing.

1. A referendum about housing for refugees in which they can’t take part? No way.

Asylum seekers are not entitled to vote and can’t take part in a referendum. Inhabitants organized in the “Initiatives for Integration” IFI have declared that they would act “in the interest of refugees” when opposing big housing complexes. De facto, however, the refugees are locked out. Such a referendum is an assault on basic rights of refugees – and on the right to the city.

2. The misery in the refugee camps admits no delay.

The miserable situation in containers, warehouses, ex-DIY-markets and other mass shelters has to be stopped as fast as possible. Even if we criticize the concrete planning of the Hamburg senate: Its decision to react quickly is right. Hamburg needs 79000 accomodations until the end of 2016. And this is only the official number. The misery in the camps has to be eliminated by conversion of existing houses as well as by building new housing. As fast, as much, as central, as high as necessary and possible.

3. The counterproposals can’t replace the emergency measures.

To achieve that it may be appropriate to realize new housing by law enforcement. It would take years to finish the needed accomodations through the usual planning law. Of course there’s good reason to be sceptical about the new housing complexes. They are mostly situated on the outskirts, feature unimaginative architecture, and little has been done to involve the communities affected, not to speak of the refugees themselves that will have to live there. But yet: the counterproposals of the protesting inhabitants and the initiatives organized in IFI are not enough to supply the much needed housing for the refugees. A “quarter mix” (that is: a quarter of newly built flats for refugees) or the “offers of real estate owners” that are allegedly rejected by the city are a mere complement to the necessary construction measures. As such they have to be discussed, like the areas that are proposed by the initiatives. However, from an “anywhere but here” position a referendum is nothing but a discussion about local limits to migration.

4. A referendum will not prevent the accomodations.

An optimistic guess is that the referendum will take place in spring 2017 at the earliest, more probably around the federal election in autumn 2017. By then people will hopefully have moved into the new accomodations which won’t be contestable by planning law. That means: a campaign for a referendum won’t prevent the planned housing complexes – but it will arouse lots of negative sentiments against them.

5. Campaigns against refugee housing attracts right-wingers and racists.

The initiatives against the big housing complexes stress time and again that they are not against refugees, that on the contrary they advocate “measures for refugee accomodation that are sustainable and reasonable for integration policies”. They say they don’t wont to talk to the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, “Alternative for Germany”, the latest right-wing party). We appreciate that – and we also think it is inappropriate to stigmatize the initiatives as racist or right-wing in the first place. However, we see in all the quarters where the new citizens movement forms how racist resentments expressed in hearings and gatherings go unchallenged and therefore influence the climate of discussions. To distance oneself from the AfD and right-wing radicalism but at the same time to provide space for their positions: This is not okay.

6. The talk of ghettos is careless and hysterical.

For years Hamburg has seen a massive compaction that displaces courtyards and natural areas. There have been protests against this development from time to time also in the quarters that now protest against refugee housing. However, the current protests are way more massive than any others before. “Parallel socities in urban ghettos have to be prevented”, the initiatives write. No matter if housing for 700 or 2000 refugees is planned like in Klein Borstel, Ottensen or Eppendorf or a huge complex for 4000 people in Neugraben-Fischbek, a quarter that doesn’t belong to the well-off: the protesting initiatives always talk of “ghettos” and demand an even distribution of accomodations throughout the city. In doing so whole communities are defamed. We plead for less hysteria. A few hundred or thousand people don’t turn a housing complex into a ghetto. We know that it’s obviously difficult to put through refugee accomodations in well-off quarters where there’s money for better lawyers and estate prices are astronomically high. However, the fact that wealthy and not so wealthy quarters now join forces does not make the distribution fairer. We worry that whereever the city plans housing for refugees it will always encounter people who think these plans are unacceptable.

7. Neither ghetto panic nor emergency planning: We need a different urbanism.

It gets back to all of us now that politicians, planners, and architects have not developed concepts of affordable, sustainable and good housing, that public housing in Germany has been more or less nothing but a funding programme for investors (no other European country did it like that). There has to be an alternative. A new urban strategy that is effective needs a new attitude. Instead of ghetto panic it’s about possibilities for the new neighbourhoods. Small sewing shops for refugees and local inhabitants, self-established kiosks, shops offering arabic delicacies, neighbourhood cafés, start-ups, local clothing chambers or workshops: all the houses that will hastily be built need free spaces in their groundfloors for such usage. We need flexibility to allow informal structures in order to get vivid quarters that offer not only housing but meeting points, space for experiments and new establishments to the communities and neighbourhoods.

8. No participation is no solution either.

In spite of warnings and forecasts by migration researchers and aid organizations the cities have not been prepared for the refugees that now arrive in Germany. The urban emergency management has been scandalous at times, and often the authorities did not react sensitively to civil society. Many volunteers who in the summer of 2015 prevented the worst through self-organized help could experience that – either at the Lageso in Berlin or in the Central Initial Reception in Hamburg-Harburg or in the emergency shelters in warehouses. People who saved the authorities’ ass with their tireless efforts were treated like annoying petitioners. It’s not without reason that the neighbours of the planned housing complexes complain about an arrogance of power. A policy that rejects participation exacerbates the conflict and is inappropriate in the face of the authorities’ omissions. Of course refugees have to be included instead of degrading them to inferior aid recipients. There’s need of dedicated planning processes with artists, urban designers, students, social workers, caregivers, volunteers and neighbourhood initiatives. Projects conceived out of Hamburg’s Right to the City movement like the PlanBude (planning booth), the once squatted and now self-managed Gängeviertel or the Fux cooperative show how collective planning leads to better results. Projects like the Grandhotel Cosmopolis Augsburg, the Haus der Statistik Berlin or the New Neighbourhood Moabit are models that have to be considered seriously. In Hamburg Refugees Welcome Karoviertel, the Clothing Chamber or the Helfergruppe Hauptbahnhof (aid group at the main station) have shown that self-organized structures can work better than the authorities machine – they have to be included.

9. Do we have a “refugee problem”? We have a housing problem!

Current plans concerning urban and social space are far behind of what’s possible technically and physically, far behind the richness of society. Hamburg’s application for the Olympics disguised its visionary void with hope for a mega-event but could not fill the void. For decades politics has ignored the housing emergency, sometimes even promoted it. To find affordable housing becomes more and more difficult even for middle class households. The market failure is obvious, and it affects especially the poor. For Refugees and Sans-papiers the situation is dramatic and often unbearable and miserable. The new programme is not yet a turning point in housing politics. With 20 billion Euro from the federal government tax money will be fed once more into the real-estate game – and be lost there. This investment should create housing that secures low rents in the long run. Housing for refugees must develop into a housing programme for all in need and with little money. Cooperatives, foundations, alternative investors like the Housing Syndicate have to be included. There have to be new concepts for public property. Pragmatism in setting up new housing is alright. But beside fast constructions there’s need for a pragmatic use of existing buildings. The demolition of the City-Hof can’t have priority now. The Axel Springer Haus could become a centrally located accomodation for refugees – the same is true for the empty Post-pyramid in the City Nord. We need a brave, determined policy for how to convert and use vacancies and existing buildings quickly and unconventionally.

10. Refugees have a right to the city.

A referendum against big housing complexes for refugees is no solution. We say: stop it! Hamburg needs neither local Seehofers in the disguise of being pro-integration nor right-wing radicals sailing on the lee side. Dissociate yourselves! The referendum boosts the wrong debate – one that frames refugees only as burden. Instead we need construction projects that have a surplus value for a quarter, that provide space for informal appropriation by the neighbourhood, that offer places for contact and platforms for exchange. Let’s develop innovative solutions together, with pragmatism and brave visions for a housing that’s socially secured indefinitely, in a city that must and will change. A great number of refugees will stay and become part of our city. They have a right to the city. Let’s push politics towards an urban planning that allows for new spaces, participation and development for us and our new neighbours. Let’s defy the brutalized self-pity of the AfD supporters.

Can we do it? No, we want it. We want a city that wants it.

Plenum of the Right to the City Network Hamburg, 9 February 2016

Plenum of the Alliance “Recht auf Stadt – never mind the papers!”, 10 February 2016